Article first published on GeekWire.

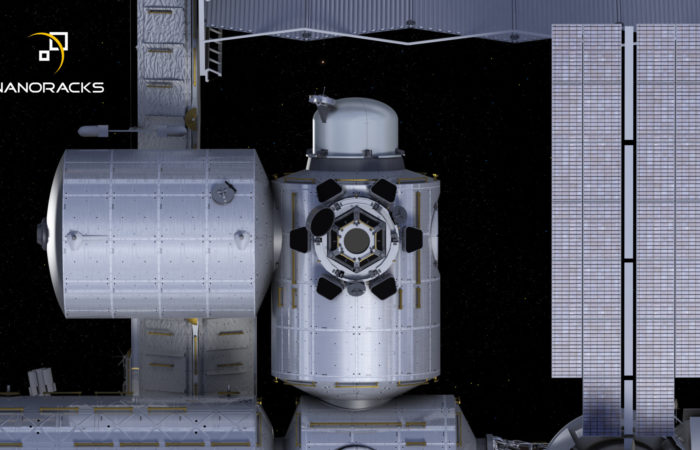

In this artist’s conception, Nanoracks’ airlock module is the knobby-looking hardware attached to a port on the International Space Station’s Tranquility module. (Nanoracks Illustration)

NASA has accepted a plan from a private venture called Nanoracks to provide the International Space Station with an air lock that would serve as its first commercial portal.

The plan could serve as the model for the eventual development of entire space stations backed by the private sector.

The Nanoracks Airlock Module is to be developed in cooperation with Boeing and could be fitted to the station’s Tranquility module by as early as 2019, NASA and Houston-based Nanoracks said today in a pair of announcements.

For years, Nanoracks has been working on logistics with NASA and the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space, or CASIS, which manages non-NASA payloads for the space station. Scores of miniaturized satellites have been deployed into orbit through an air lock on the station’s Japanese-built Kibo module with the aid of Nanoracks’ deployer.

The new air lock would let Nanoracks and its partners expand its commercial satellite deployment operation, and provide new opportunities for NASA as well as commercial ventures.

“We want to utilize the space station to expose the commercial sector to new and novel uses of space, ultimately creating a new economy in low-Earth orbit for scientific research, technology development and human and cargo transportation,” Sam Scimemi, director of the ISS Division at NASA Headquarters, said in today’s announcement. “We hope this new airlock will allow a diverse community to experiment and develop opportunities in space for the commercial sector.”

Once Nanoracks has complied with the steps outlined in a Space Act Agreement reached with NASA last year, the space agency will give the official go-ahead for installation. Today, Nanoracks announced a side agreement that gives Boeing the task of fabricating and installing a critical component of the air lock, the Passive Common Berthing Mechanism. The PCBM hardware is the standard interface for connecting space station modules.

“We are very pleased to have Boeing joining with us to develop the Airlock Module,” Nanoracks CEO Jeffrey Manber said. “This is a huge step for NASA and the U.S. space program, to leverage the commercial marketplace for low-Earth orbit, on space station and beyond, and Nanoracks is proud to be taking the lead in this prestigious venture.”

Nanoracks said San Diego-based ATA Engineering will be in charge of structural and thermal analysis, testing services and support of the air lock.

The Airlock Module is designed to be detached at a future time if desired. During last summer’s New Space conference in Seattle, Manber said it could serve as one of the initial building blocks for a commercial space station.

“That air lock can leave the station at the proper time – four, five, six years from now – and attach to a commercial piece of real estate,” Manber said at the Seattle meeting.

Other space ventures are pursuing a similar model, starting with commercial components for the space station that could be repurposed or refined for different orbital platforms.

For example, Bigelow Aerospace provided an inflatable module for testing on the space station last year under the terms of a $17.8 million contract with NASA. A larger module could serve as the first piece of a commercial space station testbed that Bigelow is developing in cooperation with United Launch Alliance.

Yet another private venture, Axiom Space, is working on a commercial orbital module that could be temporarily attached to the space station, and then detached to become the foundation for a private-sector outpost in orbit.

Nanoracks’ Manber is no stranger to space commercialization: In the late 1990s, he was the CEO of MirCorp, a company that struck a deal with the Russians for commercial orbital activities during the final days of the Mir space station.

For a time, MirCorp worked with NBC and “Survivor” producer Mark Burnett on a reality-TV space show tentatively titled “Destination Mir,” but when Mir flamed out in 2001, so did the TV project.